Brain Structure And Function

The main function of this human brain structure is to control certain visceral functions in body (including heart rate, breathing and blood pressure). Looking at the tasks assigned to pons, it serves to monitor the sleep and waking up functions while working in coordination with other parts of the nervous system.

Midbrain: Midbrain, region of the developing vertebrate brain that is composed of the tectum and tegmentum. The midbrain serves important functions in motor movement, particularly movements of the eye, and in auditory and visual processing. Mar 13, 2018 - The brain is an organ that's made up of a large mass of nerve tissue that's protected within the skull. It plays a role in just about every major.

Abstract

Background

Tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), the primary ingredient in marijuana, exerts its effects across several neurological and biological systems that interact with the endocrine system. Thus, differential effects of Δ9-THC are likely to exist based on sex and hormone levels.

Methods

We reviewed the existing literature to determine sex-based effects of Δ9-THC on neural structure and functioning.

Results

The literature demonstrates differences in male and female marijuana users on brain structure, reward processing, attention, motor coordination, and sensitivity to withdrawal. However, inconsistencies exist in the literature regarding how marijuana affects men and women differentially, and more work is needed to understand these mechanisms. While extant literature remains inconclusive, differentiation between male and female marijuana users is likely due to neurological sexual dimorphism and differential social factors at play during development and adulthood.

Conclusions

Sex has important implications for marijuana use and the development of cannabis use disorders and should be considered in the development of prevention and treatment strategies.

Introduction

Marijuana continues to be the most widely used illicit substance in the world [1, ]. Similar to other substances of abuse [], there are more male marijuana users in the USA (e.g., 54.1 %, [4]) than females historically; however, recent trends suggest that the number of female users is increasing, while the number of male users is remaining stable [5]. Interestingly, female users have been reported to develop cannabis use disorders (CUDs) more quickly after initiation of marijuana use than males (i.e., “telescoping”) [–], suggesting potential sex differences underlying the effects of Δ9-THC. These sex differences in the effects of Δ9-THC can be attributed to the interaction of the endocannabinoid and endocrine systems, as the endocannabinoid system is widely known for its modulatory role in endocrine functioning []. Alternatively, pre-morbid cognitive differences between males and females may also contribute to the sex differences observed following marijuana use. Nevertheless, these sex differences implicate the need for different prevention and treatment strategies for males and females (Table (Table11).

Table 1

Neurocognitive differences across male and female marijuana users

| Authors | Modality | Participants | Putative difference between males and females |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. (2010) [] | Double-blind, placebo-controlled (active or placebo marijuana cigarette) | 50 males, 35 females | No sex differences were observed. |

| Anderson et al. (2010) [] | Attention, cognitive flexibility, time estimation, and visuospatial processing tasks | 70 occasional marijuana users (50 % male) | No sex differences were observed, though the authors discuss a higher rate of study attrition in females. |

| Block et al. (1991) [••] | Blood sample collection, hormone analyses, and substance use questionnaires | 93 males and 56 females with either frequent, moderate, infrequent, or no marijuana use | No effect of chronic marijuana use on sex hormones (FSH, prolactin, LH, or testosterone) was found. |

| Block et al. (2000) [] | Imaging: volume | 18 adult marijuana users (50 % male) vs. 13 controls (46 % male) | Sex differences were detected in several brain volume measures. |

| Buckner et al. (2012) [] | Multi-site, marijuana smoking history, MMM, MPS, SIAS | 174 current marijuana users (57.5 % male) | Social anxiety in men was positively related to CUD problems and conforming and coping motives. Females demonstrated a positive correlation between social anxiety with social motives only. |

| Buckner et al. (2006) [] | SCID DSM-IV-TR (SCID I/NP) and self-report questionnaires | 123 undergraduates (40.7 % male) | Symptoms of social anxiety disorder were correlated with CUD symptoms in women only, and peer use of both alcohol and marijuana was found to moderate this relationship. |

| Cooper and Haney (2014) [] | Data combined from four double-blind, within-subject studies using active vs. inactive marijuana | 35 male vs. 35 female marijuana users | Women reported higher ratings of abuse-related effects relative to men under the active marijuana condition, but men and women did not differ in self-reported ratings of intoxication. |

| Copersino et al. (2010) [] | Retrospective self-report measures | 104 non-treatment seeking adult marijuana smokers (78 % male) | Females were more likely than males to report a withdrawal symptom (upset stomach, increased sex drive, marijuana craving). |

| Cousijn et al. (2012) [] | Imaging: voxel-based morphometry (VBM) | 33 heavy marijuana users (64 % male) vs. 42 controls (62 % male) | No interactions of either gray matter or white matter differences and sex was found between either of the groups. |

| Crane et al. (2013) [••] | Neuropsychological tests | 44 male vs. 25 female marijuana users | Earlier age of initiated use was related to less education, lower IQ, fewer years of maternal education, and poorer episodic memory in women only, but more lifetime marijuana use in men. |

| Felton et al. (2015) [] | Self-report and BART task over period of grades 8–12 | 115 male and 89 female adolescents | An interaction of sex and disinhibition suggested that only males who self-reported greater disinhibition showed greater increases in their marijuana use. |

| Gillespie et al. (2011) [] | Structured interviews on DSM-IV criteria of CUD | 7316 adult male and female twins | Lower factor loadings for women suggest that legal problems may discriminate better among men. |

| Guxens et al. (2007) [] | Cohort study, self-administered lifestyle questionnaire | 1056 adolescents (52.2 % male) | Fewer factors predicting marijuana use were found in males than in females. Predictive variables reflecting type of school, family situation, and academic performance were present only among girls. |

| Hernandez-Avila et al. (2004) [] | Self-report | 271 substance-dependent patients (42 % male), 38 of those were marijuana-dependent (47 % male) | No sex effects on age of onset for marijuana users were found. Women who were marijuana-dependent reported less pretreatment years of regular marijuana consumption, compared to men. Women were less likely than men to be diagnosed with current marijuana dependence. |

| Johnson et al. (2015) [] | Data from National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) 1999–2013 | 115,379 adolescents (50 % male) | Sex differences were observed to substantially decrease over time for each race/ethnicity group. |

| Jones et al. (2008) [] | Enzyme immunoassay assessment of blood | 8794 adults (94 % male) | For DUIDa suspects, the number of men far exceeded that of women, and women were older than the men. Blood THC concentration was higher in men than in women. |

| Khan et al. (2013) [] | Data from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions 2001–2002 | 3297 US adults diagnosed with lifetime CUD (63 % male) | Women with CUD presented more mood and anxiety disorders and had an increased risk for externalizing disorders. Men with CUD had an increased risk of being diagnosed with an SUD, antisocial personality disorder, or a psychiatric disorder. Men with CUD were older at remission, used more joints, and reported more CUD symptoms than women. |

| Lisdahl and Price (2012) [] | Neuropsychological tests | 23 marijuana users (44 % male) vs. 35 controls (50 % male) | Female users were found to have an earlier age of onset for regular marijuana use. Male users also demonstrated a stronger relationship between both poor sequencing ability, psychomotor speed, and increased marijuana use, even though both male and female users had similar levels of past year marijuana use. |

| McDonald et al. (2003) [] | Double-blind, placebo conditions, 7.5 or 15 mg THC capsule. Stop, Go/No-Go, delay discounting, and time estimation tasks | 37 healthy recreational marijuana users (49 % male) | No significant sex differences in performance on the impulsivity measures were observed. |

| McQueeny et al. (2011) [] | Imaging: sMRI | 35 marijuana users vs. 47 controls (both groups 77 % male) | Female marijuana users had larger right amygdala volumes and more internalizing symptoms than female controls, while male users had similar volumes to male controls. For female controls and males, worse mood/anxiety was linked to smaller right amygdala volume, whereas more internalizing problems were associated with greater right amygdala volume in female marijuana users only. |

| Medina et al. (2009) [] | Imaging: MRI | 16 marijuana users (75 % male) vs. 16 controls | Female users presented more lifetime drinking episodes and symptoms of alcohol dependence. Male users showed smaller PFC volumes while female users displayed larger PFC volumes compared to their same-sex controls. |

| Noack et al. (2011) [] | Internet survey of use characteristics | 843 current cannabis-using students (70.6 % male) | Marijuana use with a water pipe was more often reported by males, while use before sleep was more often reported by females. When rating the social contexts of their marijuana use, women reported more use “with strangers” than men. |

| Pedersen et al. (2001) [] | Longitudinal study of conduct and cannabis use | 2436 adolescents (50 % male) | Conduct problems had an impact on marijuana initiation, with a noticeably stronger effect in females. For females, covert and aggressive conduct problems had robust effects, while in males, serious conduct had a moderate effect. |

| Pope et al. (1997) [] | Visuospatial memory task | 25 heavy marijuana users vs. 30 light marijuana users | Heavy marijuana-using women have impaired memory compared to light marijuana-using women, but there was no effect in men. |

| Price et al. (2015) [] | Imaging: MRI | 27 marijuana users (56 % male) vs. 32 controls (44 % male) | No significant sex interactions were found. |

| Roser et al. (2009) [] | Double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study: psychomotor performance using finger-tapping test series | 24 healthy volunteers (50 % male) | Males showed faster left-handed taps than females after ∆9-THC condition. Females showed greater variability in tapping speed after THC administration compared to placebo. No sex differences in the tapping frequencies under the placebo condition were found. Female subjects revealed a higher AIR-Scale score under ∆9-THC, but not under MJ extract. Overall, females performed worse than males for the left-hand tapping frequencies, demonstrated higher levels of plasma THC metabolites, and reported greater perception of intoxication compared to males. |

| Schepis et al. (2011) [] | Cross-sectional statewide survey of adolescent risk behavior | 4523 public high school students (48.2 % male) | African-American males and Caucasian females were more likely to use marijuana than their counterparts of the same race, while Asian females were less likely to use. Males with depression and anhedonia in the past year had greater odds of marijuana use in the past year as well. Overall, females also demonstrated more rapid transition from initiation to regular marijuana use. |

| Skosnik et al. (2006) [] | EEG: visual function via SSVEP | 17 marijuana users (59 % male) vs. 16 healthy drug naïve controls (38 % male) | No sex differences were observed in the marijuana group for any substance use data. A main effect of sex was observed, indicating that females displayed a larger SSVEP response. A sex-by-group interaction was observed at 18 Hz, indicating that marijuana use reduced 18 Hz spectral power in females, but not in males. Overall, these findings suggest that attention may be more impaired in male marijuana users. |

| Tu et al. (2008) [] | Cross-sectional survey conducted in 2004 | 8225 students grade 7–12 (50 % male) | Aboriginal boys but not girls were more likely to use marijuana. Marijuana use was associated with higher school grade among boys, but not girls, and girls who used marijuana were more likely to report poorer mental health than boys. |

| Wetherill et al. (2015) [••] | Imaging: fMRI | 44 treatment-seeking, marijuana-dependent adults (61 % male) | Both sexes responded similarly to backward-masked marijuana cues > neutral cues, but for women, activity in the insula during this task correlated with MJ craving, while left OFC was inversely correlated with craving. For men, activity in the striatum during this task correlated with craving. |

| Zalesky et al. (2012) [] | imaging: MRI axonal fiber connectivity | 59 marijuana users (47 % male) vs. 33 matched controls (42 % male) | No significant sex differences or sex by group interactions were found. |

aDriving under the influence of drugs

Interaction Between Marijuana and Hormones: Mechanism for Sex Effects

The endocannabinoid system modulates the hypothalamic pituitary gonadal (HPG) axis. Animal studies have demonstrated that when Δ9-THC binds to cannabinoid receptors on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) releasing cells in the hypothalamus, it has differential downstream effects in men and women. In females, there have been reports of Δ9-THC both stimulating and suppressing the secretion of luteinizing hormone, which not only indicates variable effects at different stages of the menstrual cycle [–].

Studies in humans have been inconsistent, however. For example, in chronic male marijuana users, decreased testosterone has been shown [], but has not been replicated []. Further, one study found no effect of chronic marijuana use on sex hormones in males and females, including follicle stimulating hormone, prolactin, luteinizing hormone, or testosterone [••]. In all, hormonal differences between men and women should be considered as a mechanism for differential effects of Δ9-THC on brain structure and function.

Sex Differences on Brain Structures of Marijuana Users

Sexual dimorphism in the human brain is widely reported. For example, brain development is different between sexes such that total brain size peaks between 10 and 11 years of age in females, while total brain size peaks at 14 to 15 years of age in males [••, ]. Regarding overall brain tissue, an interaction between white and gray matter development and sex has been noted where prefrontal cortex (PFC) gray matter volume in females peaks 1–2 years earlier than in males, while males demonstrate greater age-related increases in white matter []. Brain regions specific to reward also develop differently between males and females. Amygdala volume increases in males as a function of androgen receptor density, while estrogen receptor density in the female hippocampus results in greater female hippocampal growth []. Thus, sex differences in brain structure may create a variable environment for Δ9-THC especially during periods of neural development when the brain is more vulnerable to structural and/or functional changes [4, ••], such as in synaptic pruning. For example, in a study of adolescent (age 16–18) marijuana users, females had greater PFC volume than males, which was associated with impaired executive functioning, suggesting that sex moderates the relationship between marijuana use and PFC volume []. Similarly, another study found larger amygdala volumes in female adolescent marijuana users relative to non-users, which was not observed in male users []. Other studies, however, have not found similar interactions with sex [].

In adults, while marijuana use has been associated with alterations in specific brain areas [], differences between sexes have only been found on the whole brain level (e.g., total whole brain volume). In a study by Block and colleagues (2000), no effect of user vs. non-user status or sex on total brain tissue volume was found, although total intracranial volume, total intracranial tissue, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and combined cerebral gray matter were found to be higher in male marijuana users than in female marijuana users []. In a study using voxel-based morphometry (VBM), Cousijn et al. (2012) found no interactions of either gray matter or white matter differences and sex between groups [].

In sum, the literature on sex-based differences in brain structure is limited. However, the existing studies suggest that male and female marijuana users have differences in brain structure, particularly in regions involved in reward processing. Differences in adolescent male and female users may be due to the sensitivity of this neural developmental period to Δ9-THC as alterations have been noted in mesocorticolimbic regions. However, there are inconsistencies in the literature. Future studies in adult marijuana users are needed to determine whether differences exist in localized areas of the brain.

Sex Differences on Brain Function of Marijuana Users

The ubiquitous nature of the endocannabinoid system suggests that effects of Δ9-THC may span wide-ranging neural processes. In this article, we focus on each of the cognitive processes most widely examined in marijuana users and report sex-based differences demonstrated in the literature.

Craving

Cannabinoids act directly on the nucleus accumbens triggering the release of dopamine in the mesolimbic “reward” circuit in the same manner as other drugs of abuse []. Though the mechanism is the same in males and females, evidence suggests differences in activation. For example, Cooper et al. (2014) demonstrated that despite no difference in levels of intoxication, females reported greater subjective positive effects than males (i.e., feeling “good,” and that they would “take it again”) []. Similarly, while both sexes experience subjective craving, Wetherill et al. (2015) demonstrated that this process might occur differently between treatment-seeking marijuana-dependent males and females [••]. In their study, they used a backward masking of marijuana cues that allows for subconscious but not conscious processing of visual stimuli. Preliminary analyses showed greater response in the striatum, left hippocampus and amygdala, and left lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) of females compared to males when exposed to the masked marijuana cues relative to masked neutral cues. Thus, females appear to exhibit greater cortical involvement in valuation of cues relative to males. Further analyses also revealed differences in correlations between neural response to marijuana cues and subjective craving with the most notable difference a negative correlation in the left lateral OFC in female users and an absence of a negative correlation in males. The negative correlation in females was interpreted as top-down cognitive control during exposure to cues, or the incorporation of previously learned patterns via higher-order (i.e., incorporating more information globally) brain regions in processing these cues. The lack of such processing in males suggests the lack of recruitment of these higher-order brain regions. In conclusion, the authors suggest that incorporation of top-down neural functioning may be a viable treatment approach, as pattern recognition may help those with CUDs (presumably males more than females) identify the deleterious effects of marijuana use [••].

Inhibitory Control

Impulsivity is a known risk fact for CUD [] and may differ between the sexes in some components (i.e., sensation seeking) but not others (i.e., delay discounting) []. The concept of impulsivity is broad and encompasses several cognitive domains that characterize one’s ability to control one’s behavior. In a study of adolescent marijuana users, an interaction between self-reported behavioral disinhibition (a composite score of measures of impulsivity and sensation seeking) and sex was found, such that males with higher self-reported disinhibition were more likely to use marijuana than females (with higher self-reported disinhibition?) []. However, because impulsivity wanes through maturation, it would be important to determine if this trend continues in adulthood []. Currently, existing studies in adult marijuana users do not demonstrate sex differences in domains of impulsivity during acute Δ9-THC intoxication. For example, McDonald and colleagues did not find differences between adult male and female marijuana users on inhibitory control tasks including (i) the Stop Signal task, which measures the motor response inhibition to an ongoing motor response, (ii) the Go/No-Go task, which measures the ability to withhold a motor response to prepotent stimuli, or (iii) the Delay Discounting Task, which measures the cognitive ability to delay immediate, smaller rewards for larger, later rewards []. These inhibitory control functions may also be referred to as “stopping impulsivity” and “waiting impulsivity” respectively, and while both circuits implicate mesolimbic dopaminergic circuitry, the former involves motor regions while the latter involves top-down, cortical control of behavior []. The lack of sex effects in these domains suggests that Δ9-THC intoxication does not have unique sex effects on either motor or cognitive control [].

In sum, the broad concept of impulsivity need to be disentangled in order to better understand the sex effects of marijuana on domains of impulsivity. However, in adolescents, general impulsive behavior is differentially linked to marijuana use between sexes.

Motor Coordination

Given the abundance of cannabinoid receptors in brain motor control regions such as the basal ganglia and cerebellum, it is not surprising that studies have shown acute effects of THC on motor coordination and control, including how these may differ between the sexes. One task used to examine this is a finger-tapping frequency task that is designed to examine fine motor coordination. Using this task, Roser and colleagues (2009) found that males demonstrate significantly faster left-hand tapping than females after Δ9-THC administration, but not right (dominant) hand tapping []. Females in this study also reported higher subjective intoxication ratings and had higher concentrations of THC metabolites in their blood after being administered the same amount of Δ9-THC as males. The authors concluded that, while no effect was seen with the dominant hand, perhaps greater intoxication in females is related to greater “functional instability” in their non-dominant hand. Another study examining neuropsychological functioning in marijuana using adults found that male users demonstrated a stronger relationship between both poor sequencing ability, psychomotor speed, and increased marijuana use, even though both male and female users had similar levels of past year marijuana use [].

Aspects of motor coordination can also be explored using driving tasks, although other cognitive processes such as attention likely confound overall performance. For example, Anderson et al. (2010) tested acute effects of Δ9-THC before and after smoking a marijuana or placebo cigarette [] during a distracted driving simulator task. Participants who received the placebo cigarettes demonstrated learning effects wherein they exhibited improved performance the second time the test was administered, whereas participants administered marijuana cigarettes did not. However, no sex differences were noted in performance. The lack of sex differences in the driving task suggests that complex motor skills may not be as sensitive to sex effects of Δ9-THC as in those that measure fine motor coordination [].

In sum, studies of motor coordination suggest that fine motor coordination differences between sexes may be related to degree of intoxication. Future studies should control for levels of intoxication and determine whether effects remain despite similar intoxication levels. More complex motor tasks should control for confounding effects of higher-order processes that may influence fine motor coordination.

Memory

The literature widely supports the effects of marijuana on memory, particularly short-term memory in intoxicated individuals []. Studies focused on sex differences on memory functions in marijuana users suggest domain-specific effects. However, such findings have not been consistent. For instance, Pope et al. (1997) showed that heavy (smoked 29 out of the past 30 days) marijuana using females had impaired memory of visual checkerboard patterns compared to light (smoked one out of the past 30 days) marijuana using females, whereas no difference between heavy- and light-using males were found following a supervised abstinence period of at least 19 h. In addition, no difference was found between the sexes (i.e., heavy-using women vs. heavy-using men, or light-using women vs. light-using men) []. On the contrary, in a study examining acute effects of marijuana, Anderson et al. (2010) did not find a difference in visuospatial processing between sexes []. Similar to motor coordination, inconsistencies in differences in memory performance could be due to differences in levels of intoxication.

Attention

While impaired attention has been documented in marijuana users [], only one study to date documents differences between the sexes. Skosnik and collegues (2006) used electroencephalography (EEG) to examine attention via the steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP), particularly the N160 response, in current (at least one use per week) marijuana users. This response to visual stimuli is thought to measure attention by means of visual processing. Overall, the N160 response was lower in marijuana users compared to controls. Additionally, it was found to be lowest in the male marijuana users []. This suggests that attention may be more impaired in male marijuana users than in female users. However, two caveats were noted. First, males reported using 11.2 joints per week on average, which is greater than females, who averaged 9.3. Second, females’ menstrual cycle was not documented, which may affect visual processing [].

There is limited literature suggesting general differences in attention between males and females, particularly on memory performance during divided attention [], and during attention related to visual motor processing [56]. In light of this, given marijuana’s known general effects on attention, future work should examine potential differences between men and women both during acute intoxication and after chronic marijuana use.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Although the number of studies that directly examine sex differences in marijuana users is limited (fewer than 30), the existing literature shows differences in brain structure and function. Differences in brain structure and function between male and female marijuana users show a complex picture that likely reflects the complicated sexual dimorphism that occurs in all biological systems. Thus, differential effects of marijuana based on sex may be different on multiple levels.

Our review revealed inconsistencies in the existing literature, which could be attributed to a number of factors. First, there may be underlying risk factors that are independent of sex. For example, risk factors for CUDs may be more prevalent within the subpopulation of women who do use marijuana and thus contribute toward CUDs. This is supported by the greater hedonic responses to marijuana reported by female users. However, the neural processes involved in this etiology are complex and require extensive further examination. Compounding the unique effects of marijuana on sex are multiple factors that have yet to be delineated. Studies have already begun to illustrate the importance of age of initiation of use []. Male and female brains develop at different rates and in different ways invariably resulting in differential effects of marijuana on each sex depending on age of exposure. Another limitation in studies of acute effects of THC in sexes is due to differences in subjective measures of intoxication. For example, D’Souza and colleagues identified variable reports in euphoria, perceptual alterations, feelings of anxiety, and disorganization of thoughts among acutely intoxicated participants. Variability between participants in these symptoms would likely confound effects of THC on outcome measures [].

A final consideration worth noting is the self-selection in participants that are likely to confound study findings. As marijuana is still illegal in the majority of the USA, recruitment for marijuana using participants has its challenges. There may be differential effects of social norms on men and women that result in imbalanced representations between these sexes. One study revealed that “attempts were made to recruit equal numbers of men and women, however, fewer women expressed interest in participating in the study” []. Additionally, the women that do overcome aversion to admitting they use marijuana may demonstrate different personality traits than female marijuana users at large and could therefore be skewing the documented data. Thus, there may be limited generalizability in existing findings.

In conclusion, the differential effects of marijuana on the structure and function of male and female brains remains elusive. Some effects have been shown concerning attention, motor coordination, and impulsivity, but further work is needed to disentangle the mélange of variables affecting sex differences in marijuana users. Future directions should include controls for quantity of marijuana and ideally THC/CBD concentration, as well as females’ menstrual cycles, and age of initiation. Clinicians should consider the differences put forth by existing literature.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Ariel Ketcherside, Jessica Baine, and Francesca Filbey declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cannabis

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

Overview

The brain is an amazing three-pound organ that controls all functions of the body, interprets information from the outside world, and embodies the essence of the mind and soul. Intelligence, creativity, emotion, and memory are a few of the many things governed by the brain. Protected within the skull, the brain is composed of the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem.

The brain receives information through our five senses: sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing - often many at one time. It assembles the messages in a way that has meaning for us, and can store that information in our memory. The brain controls our thoughts, memory and speech, movement of the arms and legs, and the function of many organs within our body.

The central nervous system (CNS) is composed of the brain and spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is composed of spinal nerves that branch from the spinal cord and cranial nerves that branch from the brain.

Brain

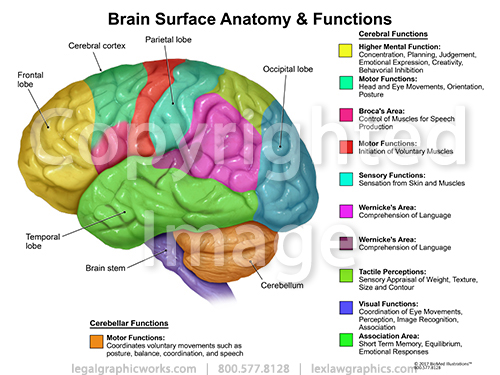

The brain is composed of the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem (Fig. 1).

Cerebrum: is the largest part of the brain and is composed of right and left hemispheres. It performs higher functions like interpreting touch, vision and hearing, as well as speech, reasoning, emotions, learning, and fine control of movement.

Cerebellum: is located under the cerebrum. Its function is to coordinate muscle movements, maintain posture, and balance.

Brainstem: acts as a relay center connecting the cerebrum and cerebellum to the spinal cord. It performs many automatic functions such as breathing, heart rate, body temperature, wake and sleep cycles, digestion, sneezing, coughing, vomiting, and swallowing.

Right brain – left brain

The cerebrum is divided into two halves: the right and left hemispheres (Fig. 2) They are joined by a bundle of fibers called the corpus callosum that transmits messages from one side to the other. Each hemisphere controls the opposite side of the body. If a stroke occurs on the right side of the brain, your left arm or leg may be weak or paralyzed.

Not all functions of the hemispheres are shared. In general, the left hemisphere controls speech, comprehension, arithmetic, and writing. The right hemisphere controls creativity, spatial ability, artistic, and musical skills. The left hemisphere is dominant in hand use and language in about 92% of people.

Lobes of the brain

The cerebral hemispheres have distinct fissures, which divide the brain into lobes. Each hemisphere has 4 lobes: frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital (Fig. 3). Each lobe may be divided, once again, into areas that serve very specific functions. It’s important to understand that each lobe of the brain does not function alone. There are very complex relationships between the lobes of the brain and between the right and left hemispheres.

Frontal lobe

- Personality, behavior, emotions

- Judgment, planning, problem solving

- Speech: speaking and writing (Broca’s area)

- Body movement (motor strip)

- Intelligence, concentration, self awareness

Parietal lobe

- Interprets language, words

- Sense of touch, pain, temperature (sensory strip)

- Interprets signals from vision, hearing, motor, sensory and memory

- Spatial and visual perception

Occipital lobe

- Interprets vision (color, light, movement)

Temporal lobe

- Understanding language (Wernicke’s area)

- Memory

- Hearing

- Sequencing and organization

Language

In general, the left hemisphere of the brain is responsible for language and speech and is called the 'dominant' hemisphere. The right hemisphere plays a large part in interpreting visual information and spatial processing. In about one third of people who are left-handed, speech function may be located on the right side of the brain. Left-handed people may need special testing to determine if their speech center is on the left or right side prior to any surgery in that area.

Aphasia is a disturbance of language affecting speech production, comprehension, reading or writing, due to brain injury – most commonly from stroke or trauma. The type of aphasia depends on the brain area damaged.

Broca’s area: lies in the left frontal lobe (Fig 3). If this area is damaged, one may have difficulty moving the tongue or facial muscles to produce the sounds of speech. The person can still read and understand spoken language but has difficulty in speaking and writing (i.e. forming letters and words, doesn't write within lines) – called Broca's aphasia.

Wernicke's area: lies in the left temporal lobe (Fig 3). Damage to this area causes Wernicke's aphasia. The individual may speak in long sentences that have no meaning, add unnecessary words, and even create new words. They can make speech sounds, however they have difficulty understanding speech and are therefore unaware of their mistakes.

Cortex

The surface of the cerebrum is called the cortex. It has a folded appearance with hills and valleys. The cortex contains 16 billion neurons (the cerebellum has 70 billion = 86 billion total) that are arranged in specific layers. The nerve cell bodies color the cortex grey-brown giving it its name – gray matter (Fig. 4). Beneath the cortex are long nerve fibers (axons) that connect brain areas to each other — called white matter.

The folding of the cortex increases the brain’s surface area allowing more neurons to fit inside the skull and enabling higher functions. Each fold is called a gyrus, and each groove between folds is called a sulcus. There are names for the folds and grooves that help define specific brain regions.

Deep structures

Pathways called white matter tracts connect areas of the cortex to each other. Messages can travel from one gyrus to another, from one lobe to another, from one side of the brain to the other, and to structures deep in the brain (Fig. 5).

Hypothalamus: is located in the floor of the third ventricle and is the master control of the autonomic system. It plays a role in controlling behaviors such as hunger, thirst, sleep, and sexual response. It also regulates body temperature, blood pressure, emotions, and secretion of hormones.

Pituitary gland: lies in a small pocket of bone at the skull base called the sella turcica. The pituitary gland is connected to the hypothalamus of the brain by the pituitary stalk. Known as the “master gland,” it controls other endocrine glands in the body. It secretes hormones that control sexual development, promote bone and muscle growth, and respond to stress.

Pineal gland: is located behind the third ventricle. It helps regulate the body’s internal clock and circadian rhythms by secreting melatonin. It has some role in sexual development.

Thalamus: serves as a relay station for almost all information that comes and goes to the cortex. It plays a role in pain sensation, attention, alertness and memory.

Basal ganglia: includes the caudate, putamen and globus pallidus. These nuclei work with the cerebellum to coordinate fine motions, such as fingertip movements.

Limbic system: is the center of our emotions, learning, and memory. Included in this system are the cingulate gyri, hypothalamus, amygdala (emotional reactions) and hippocampus (memory).

Memory

Memory is a complex process that includes three phases: encoding (deciding what information is important), storing, and recalling. Different areas of the brain are involved in different types of memory (Fig. 6). Your brain has to pay attention and rehearse in order for an event to move from short-term to long-term memory – called encoding.

- Short-term memory, also called working memory, occurs in the prefrontal cortex. It stores information for about one minute and its capacity is limited to about 7 items. For example, it enables you to dial a phone number someone just told you. It also intervenes during reading, to memorize the sentence you have just read, so that the next one makes sense.

- Long-term memory is processed in the hippocampus of the temporal lobe and is activated when you want to memorize something for a longer time. This memory has unlimited content and duration capacity. It contains personal memories as well as facts and figures.

- Skill memory is processed in the cerebellum, which relays information to the basal ganglia. It stores automatic learned memories like tying a shoe, playing an instrument, or riding a bike.

Ventricles and cerebrospinal fluid

The brain has hollow fluid-filled cavities called ventricles (Fig. 7). Inside the ventricles is a ribbon-like structure called the choroid plexus that makes clear colorless cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). CSF flows within and around the brain and spinal cord to help cushion it from injury. This circulating fluid is constantly being absorbed and replenished.

There are two ventricles deep within the cerebral hemispheres called the lateral ventricles. They both connect with the third ventricle through a separate opening called the foramen of Monro. The third ventricle connects with the fourth ventricle through a long narrow tube called the aqueduct of Sylvius. From the fourth ventricle, CSF flows into the subarachnoid space where it bathes and cushions the brain. CSF is recycled (or absorbed) by special structures in the superior sagittal sinus called arachnoid villi.

A balance is maintained between the amount of CSF that is absorbed and the amount that is produced. A disruption or blockage in the system can cause a build up of CSF, which can cause enlargement of the ventricles (hydrocephalus) or cause a collection of fluid in the spinal cord (syringomyelia).

Skull

The purpose of the bony skull is to protect the brain from injury. The skull is formed from 8 bones that fuse together along suture lines. These bones include the frontal, parietal (2), temporal (2), sphenoid, occipital and ethmoid (Fig. 8). The face is formed from 14 paired bones including the maxilla, zygoma, nasal, palatine, lacrimal, inferior nasal conchae, mandible, and vomer.

Inside the skull are three distinct areas: anterior fossa, middle fossa, and posterior fossa (Fig. 9). Doctors sometimes refer to a tumor’s location by these terms, e.g., middle fossa meningioma.

Similar to cables coming out the back of a computer, all the arteries, veins and nerves exit the base of the skull through holes, called foramina. The big hole in the middle (foramen magnum) is where the spinal cord exits.

Cranial nerves

The brain communicates with the body through the spinal cord and twelve pairs of cranial nerves (Fig. 9). Ten of the twelve pairs of cranial nerves that control hearing, eye movement, facial sensations, taste, swallowing and movement of the face, neck, shoulder and tongue muscles originate in the brainstem. The cranial nerves for smell and vision originate in the cerebrum.

The Roman numeral, name, and main function of the twelve cranial nerves:

Number | Name | Function |

I | olfactory | smell |

II | optic | sight |

III | oculomotor | moves eye, pupil |

IV | trochlear | moves eye |

V | trigeminal | face sensation |

VI | abducens | moves eye |

VII | facial | moves face, salivate |

VIII | vestibulocochlear | hearing, balance |

IX | glossopharyngeal | taste, swallow |

X | vagus | heart rate, digestion |

XI | accessory | moves head |

XII | hypoglossal | moves tongue |

Meninges

The brain and spinal cord are covered and protected by three layers of tissue called meninges. From the outermost layer inward they are: the dura mater, arachnoid mater, and pia mater.

Dura mater: is a strong, thick membrane that closely lines the inside of the skull; its two layers, the periosteal and meningeal dura, are fused and separate only to form venous sinuses. The dura creates little folds or compartments. There are two special dural folds, the falx and the tentorium. The falx separates the right and left hemispheres of the brain and the tentorium separates the cerebrum from the cerebellum.

Arachnoid mater: is a thin, web-like membrane that covers the entire brain. The arachnoid is made of elastic tissue. The space between the dura and arachnoid membranes is called the subdural space.

Pia mater: hugs the surface of the brain following its folds and grooves. The pia mater has many blood vessels that reach deep into the brain. The space between the arachnoid and pia is called the subarachnoid space. It is here where the cerebrospinal fluid bathes and cushions the brain.

Blood supply

Blood is carried to the brain by two paired arteries, the internal carotid arteries and the vertebral arteries (Fig. 10). The internal carotid arteries supply most of the cerebrum.

The vertebral arteries supply the cerebellum, brainstem, and the underside of the cerebrum. After passing through the skull, the right and left vertebral arteries join together to form the basilar artery. The basilar artery and the internal carotid arteries “communicate” with each other at the base of the brain called the Circle of Willis (Fig. 11). The communication between the internal carotid and vertebral-basilar systems is an important safety feature of the brain. If one of the major vessels becomes blocked, it is possible for collateral blood flow to come across the Circle of Willis and prevent brain damage.

The venous circulation of the brain is very different from that of the rest of the body. Usually arteries and veins run together as they supply and drain specific areas of the body. So one would think there would be a pair of vertebral veins and internal carotid veins. However, this is not the case in the brain. The major vein collectors are integrated into the dura to form venous sinuses — not to be confused with the air sinuses in the face and nasal region. The venous sinuses collect the blood from the brain and pass it to the internal jugular veins. The superior and inferior sagittal sinuses drain the cerebrum, the cavernous sinuses drains the anterior skull base. All sinuses eventually drain to the sigmoid sinuses, which exit the skull and form the jugular veins. These two jugular veins are essentially the only drainage of the brain.

Cells of the brain

The brain is made up of two types of cells: nerve cells (neurons) and glia cells.

Nerve cells

There are many sizes and shapes of neurons, but all consist of a cell body, dendrites and an axon. The neuron conveys information through electrical and chemical signals. Try to picture electrical wiring in your home. An electrical circuit is made up of numerous wires connected in such a way that when a light switch is turned on, a light bulb will beam. A neuron that is excited will transmit its energy to neurons within its vicinity.

Neurons transmit their energy, or “talk”, to each other across a tiny gap called a synapse (Fig. 12). A neuron has many arms called dendrites, which act like antennae picking up messages from other nerve cells. These messages are passed to the cell body, which determines if the message should be passed along. Important messages are passed to the end of the axon where sacs containing neurotransmitters open into the synapse. The neurotransmitter molecules cross the synapse and fit into special receptors on the receiving nerve cell, which stimulates that cell to pass on the message.

Glia cells

Glia (Greek word meaning glue) are the cells of the brain that provide neurons with nourishment, protection, and structural support. There are about 10 to 50 times more glia than nerve cells and are the most common type of cells involved in brain tumors.

- Astroglia or astrocytes are the caretakers — they regulate the blood brain barrier, allowing nutrients and molecules to interact with neurons. They control homeostasis, neuronal defense and repair, scar formation, and also affect electrical impulses.

- Oligodendroglia cells create a fatty substance called myelin that insulates axons – allowing electrical messages to travel faster.

- Ependymal cells line the ventricles and secrete cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

- Microglia are the brain’s immune cells, protecting it from invaders and cleaning up debris. They also prune synapses.

Sources & links

If you have more questions, please contact Mayfield Brain & Spine at 800-325-7787 or 513-221-1100.

Links

Brain Structure And Function

updated > 4.2018

reviewed by > Tonya Hines, CMI, Mayfield Clinic, Cincinnati, Ohio

Brain Structure And Function Quizlet

Mayfield Certified Health Info materials are written and developed by the Mayfield Clinic. We comply with the HONcode standard for trustworthy health information. This information is not intended to replace the medical advice of your health care provider.